- Home

- Mary Elise Sarotte

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe Page 2

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe Read online

Page 2

I have chosen to investigate this particular reordering moment by looking at evidence from all key actors. Obviously, this means examining the role of the United States and the Soviet Union; but as Ellen Schrecker has complained in a book lamenting U.S.-centric Cold War studies, the fact that East Europeans “might have also had a hand in the process” does not figure often enough in the story.4 The same could be said of West Europeans as well. As a result, this book will try to do justice to a number of significant parties on both sides of the East-West divide, not just the United States and the Soviet Union. It offers an international study of 1989 and 1990 based on research in archives, private papers, and sound and video recordings from—going roughly East to West—Moscow, Warsaw, Dresden, Berlin, Leipzig, Hamburg, Koblenz, Bonn, Paris, London, Cambridge, Princeton, Washington, College Station, and Simi Valley. On top of this, it draws on the published documents available from those locations, and from Beijing, Budapest, Prague, and other places as well.

The historical evidence for this time period is unusually, indeed astonishingly, rich for one so recent. Why is so much material available so soon after events? There appear to be three reasons for this. First, the overthrow of the established Cold War order took place both from above and below. My sources consequently consist of a number of items that have never been classified: broadcasts, manifestos, peace prayers, protest signs, and transcripts of meetings of round table and opposition groups, to name a few. Because of this, the research for this volume went beyond the usual sites of “high politics,” and included work in media archives as well as the memorabilia, letters, and notes of individual church members, dissidents, and protesters.5

Second, a substantial amount of material emerged from now-defunct political entities—namely, the former member states of the Warsaw Pact, and even the Warsaw Pact itself—which either gave up or lost the ability to keep their materials hidden away from public view for the usual closure period. Particularly useful were the Russian materials from the Gorbachev Foundation, the volume of documents on divided Germany published by former Secretary General Mikhail Gorbachev and his adviser Anatoly Chernyaev, and the so-called Fond 89 assembled later by Russian leader Boris Yeltsin.6 The East German party and secret police archives were essential sources as well, as were documents from other Warsaw Pact member states.

Although former Soviet Bloc materials are obviously useful to scholars, they can also lure historians into engaging in a kind of “victor’s justice”—namely, the process of writing history from the point of view of the still-existing states based on the sources of the disappeared. To counter this problem, I scrutinized not just the records of defunct regimes but also of some of the most powerful entities in the world today. I was able to do so by reading published documents where available, and filing Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests or their equivalents where they were not; in the end, four countries released materials to me. I also piggybacked on FOIAs filed by others.

The surprising and extensive willingness of various gatekeepers to let me (and others) see such documents before the end of the usual classification period seems to be a result of the notion that success has many fathers. In other words, the end of the Cold War, from the Western leaders’ point of view, was a triumph. They hoped to get credit for it, of course; but they also wanted to get information about the peaceful transition of 1989–90 into the public domain, in the hopes that its lessons could be learned. As a result, many of the politicians involved, most notably former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, declassified and even published thousands of pages of documents. The appearance of Kohl’s chancellery papers, documenting his past successes as a leader, occurred at the same time as a particularly close election, one that he eventually lost. These papers represent an extraordinarily useful resource. And thanks to the German Federal Archive’s decision to allow me early access to some of the state documents that are not yet open to the public, I was able to read these published sources in the context of the original collections.7

Similarly, the George H. W. Bush Presidential Library in College Station, Texas, has approved FOIA requests for thousands of pages related to 1989–90. While many parts remain closed or redacted, the open portions nonetheless provide insight into top-level U.S. foreign policymaking, especially when read in conjunction with the detailed study written by U.S. participants Condoleezza Rice and Philip Zelikow.8 I was able to read these Bush documents together with the extensive personal papers of the former secretary of state, James A. Baker III, thanks to his decision to grant me access to them. The Bush and Baker papers gave insight into the two critical components of U.S. foreign policymaking in this period—namely, the White House and National Security Council on the one hand, and the State Department on the other.9

West European leaders besides Kohl have been somewhat reticent, but the relatively recent British FOIA means that this study can draw on some of the first materials released from Number 10 Downing Street under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher as well as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office under Douglas Hurd; the two did not see eye to eye in this period, so it is useful to look at both. Four years of petitions and appeals in the United Kingdom (UK) succeeded just in time for inclusion of both sides in this publication.10 France does not have such legislation officially, but my individual petition for early archival access was approved as well. There is also a limited selection of primary documents published by François Mitterrand.11 In addition, some top-level materials are available from Beijing.12

On top of all of these sources, two remarkable U.S. groups have done a great service to scholars by collecting, assembling, and in many cases translating documents from these and other locations around the world. The Cold War International History Project and the National Security Archive make these items available to scholars and often distribute them in the form of “briefing books” at major conferences. I have relied on these for their fascinating materials from, among other places, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Asian states.13 In quoting these documents, any emphasis is present in the original unless otherwise stated in the note.

The usual disadvantage of work on contemporary history is the dearth of high-quality primary sources, but as explained above, that is not the case here. The advantage of work on a recent time period is the availability of interview partners. A number of participants in events were willing to let me speak with them, including Baker, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Hurd, Charles Powell, Brent Scowcroft, Horst Teltschik, Zelikow, and Robert Zoellick; a complete list may be found in the bibliography. Their insights have helped significantly in the analysis of the original source materials listed above, and some of them were even willing to read drafts of sections of this work.14 Moreover, a rich memoir literature and extensive collections of published documents from international institutions such as the Warsaw Pact, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the European Community (EC, later the European Union, or EU) have helped as well.

In using these materials, I tried to choose crucial events and investigate the evidence from them as deeply and thoughtfully as possible. My research took place in three steps. The first stage involved years of locating, petitioning for, and examining sources and interviewing participants. Then, in the second step, I condensed these sources into a digital database of the thousand most important broadcasts, documents, interview comments, and television images. The third step involved constructing a detailed analytic chronology of the events, which became the eventual basis for the narrative chapters below.15

The methodological framework for this book comes roughly from Alexander George’s concept of setting up structured, focused comparisons between suitable events.16 To cite Theda Skocpol, comparative historical analysis “is, in fact, the mode of multivariate analysis to which one resorts when there are too many variables and not enough cases.”17 Variants on such a method have characterized many of the best histories of international relations to appear in the last few decades, such as Gaddis’s Strategies of

Containment (1982), Paul Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1987), and Odd Arne Westad’s The Global Cold War (2005).18 These studies employed a similar, and similarly successful, method. They all chose one complex issue (respectively, containment, imperial growth, and wars of intervention) and compared how crucial actors attempted to master the challenges involved. Gaddis compared their strategies of containment; Kennedy compared their strategies for imperial extension, which resulted in overstretch and decline; and Westad compared strategies of intervention.

Starting with the introduction, this book will attempt the daunting task of trying to follow where they have led. It will compare strategies for re-creating order after it has broken down—an enduring problem in history. A generation of leaders faced this challenge in 1989; they saw chaos, and sought to devise and implement plans to control it as quickly as possible. I explore who succeeded and why. Obviously my time frame is different than the studies mentioned above—months instead of decades or centuries—but the method remains valid. I will leave it to the reader to determine whether or not I have used it successfully.

ABBREVIATIONS

ATTU

Atlantic-to-Urals (military zone)

CDU

Christian Democratic Union (German)

CFE

Conventional Forces in Europe (Treaty)

CIA

Central Intelligence Agency (United States)

CSCE

Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

DM

Deutsche Mark, the currency of West Germany in 1989

EC

European Community

EU

European Union

FDP

Free Democratic Party (German), also known as the Liberals

FRG

Federal Republic of Germany, or West Germany

GDR

German Democratic Republic, or East Germany

IFM

Initiative for Peace and Human Rights, German initials for (East German)

INF

Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces

KGB

Committee for State Security, Russian initials for (Soviet Union)

NATO

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NSC

National Security Council (United States)

PDS

Party of Democratic Socialism (German)

PLA

People’s Liberation Army (Chinese)

SED

Socialist Unity Party, German initials for (East German)

SNF

Short-Range Nuclear Forces

SPD

Social Democratic Party of Germany, German initials for

UK

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

USSR

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

1989

INTRODUCTION

CREATING POST–COLD WAR EUROPE: 1989 AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF ORDER

A whole generation emerged in the disappearing.

—East German Jana Hensel, age thirteen in 1989

This city, of all cities, knows the dream of freedom.

—Barack Obama, in Berlin, 20081

On November 9, 1989, the Berlin Wall opened and the world changed. Memory of that iconic instant has, unsurprisingly, retained its power despite the passage of time. Evidence of its enduring strength was apparent in the decision by a later icon of change—Barack Obama—to harness it in his own successful pursuit of one of history’s most elusive prizes, the U.S. presidency. While a candidate in 2008, he decided that the fall of the wall still represented such a striking symbol that it was worth valuable time away from American voters in a campaign summer to attach himself to it.

He also knew that lasting images had resulted from the Cold War visits of Presidents John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan to divided Berlin, and hoped to produce some of his own on a trip to the united city. In particular, Obama wanted to use the Brandenburg Gate, formerly a prominent site of the wall, as the backdrop for his first speech abroad as the clear Democratic nominee in summer 2008. However, the politics of the memory involved were still so vital that the right-of-center leader of Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel—herself a former East German—decided to prevent Obama from appropriating them. She informed him that he did not have her permission to speak at the gate. It might be too evocative and look like an attempt by the German government to influence the U.S. election. Supporters of Obama’s opponent, Senator John McCain, welcomed Merkel’s decision; they derided the Berlin visit as an act of hubris that revealed a candidate playing statesman before his time. Undeterred, Obama chose instead to deliver his address as near as possible, at the Victory Column just down the street. The less emotional venue still drew two hundred thousand people to share the experience. “This city, of all cities, knows the dream of freedom,” he told the cheering crowd. “When you, the German people, tore down that wall—a wall that divided East and West; freedom and tyranny; fear and hope—walls came tumbling down around the world. From Kiev to Cape Town, prison camps were closed, and the doors of democracy were opened.” 2 The speech and the campaign succeeded brilliantly. Later in 2008, on the night that would turn Obama into the first African American president, he even returned in spirit to Berlin. In his victory speech in Chicago, he intoned a list of great changes. After remembering the dawn of voting rights for all and the steps of the first men on the moon, he added simply, “a wall came down in Berlin.” 3

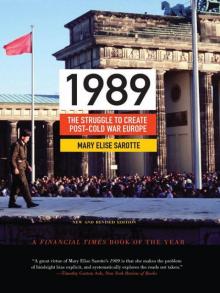

Fig. I.1. Barack Obama in Berlin, July 24, 2008. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Although Obama could celebrate the collapse of the wall as an example of peaceful change, no one knew whether or not that would be the case in 1989. Its opening had yielded not only joy but also some extremely frightening questions. Would Germans demand rapid unification in a massive nationalistic surge that would revive old animosities? Would Soviet troops in East Germany stay in their barracks? Would Gorbachev stay in power or would hard-liners oust him for watching the wall fall while failing to get anything in return? Would Communist countries in the rest of Central Europe subsequently expire violently and leave bloody scars? Would centrally planned economies immediately implode and impoverish millions of Europeans?4 Would West European social welfare systems and market economies be able to absorb these new crowds, or be swamped by them? Would millions of young East Europeans like the thirteen-year-old Jana Hensel, who would later write the best-selling After the Wall about the shock of the transformation, be able to master the personal and psychological challenges of such a massive transition?5 Would international institutions survive the challenges to come or descend into disabling disagreements about the future?

There was little doubt, in short, that history had reached a turning point; but the way forward was not obvious. With hindsight we know that the transition stayed peaceful, but why is less clear—through design, dumb luck, or both? Put another way, how can we best understand what happened in 1989 and its aftermath?

A generation of analysts has interpreted this year as a period of closure.6 I see it differently: as a time not of ending, but of beginning. The Cold War order had long been under siege and its collapse was nearly inevitable by 1989. Yet there was nothing at all inevitable about what followed. This book seeks to explain not the end of the Cold War but the struggle to create post–Cold War Europe. It attempts to solve the following puzzles: Why were protesters on the ground able to force dramatic events to a climax in 1989? Why did the wall open on November 9? Why did the race to recast Europe afterward yield the present arrangement and not any of the numerous alternatives? Why did the “new” world order in fact look very much like the old, despite the momentous changes that had transpired?

To answer these questions, I examined the actors, ideas, images, material factors, and politics involved. Remarkable human stories emerged at every turn—from a dissident who smuggled himself back into East Germany after being thrown out, to the television j

ournalists who opened the Berlin Wall without knowing they were doing so, to the pleading of Gorbachev’s wife with a Western diplomat to protect her husband from himself, to the way that Vladimir Putin personally experienced 1989 in Dresden as a Soviet spy.

I will describe my findings in detail in the pages to come, but a few of them merit highlighting here. This book will challenge common but mistaken assumptions that the opening of the wall was planned, that the United States continuously dominated events afterward, and that the era of German reunification is now a closed chapter, without continuing consequences for the transatlantic alliance. I will show how, if there were any one individual to emerge as the single most important leader in the construction of post–Cold War Europe, it would have to be Kohl rather than Bush, Gorbachev, or Reagan; how Mitterrand was an uneasy but crucial facilitator of German unity, not its foe; and how Russia got left on the periphery as Germany united and the EC and NATO expanded, generating fateful resentments that shape geopolitics to this day. More broadly, I will question the enduring belief of U.S. policymakers that “even two decades later, it is hard to see how the process of German unification could have been handled any better.” From a purely American point of view, this belief is understandable; but it is not universally shared. The international perspective in these pages will yield a more critical interpretation of 1989–90. To cite just one example, the former British Foreign Minister Hurd does indeed think that better alternatives were conceivable. In 1989–90 there was a theoretical opportunity “which won’t come again, which Obama does not have, to remake the world, because America was absolutely at the pinnacle of its influence and success.” Put another way, “you could argue that if they had been geniuses, George Bush and Jim Baker would have sat down in 1990 and said the whole game is coming into our hands.” They would have concluded that “we’ve got now an opportunity, which may not recur, to remake the world, update everything, the UN, everything. And maybe if they had been Churchill and Roosevelt, you know, they might have done that.” But Hurd finds that “they weren’t that kind of person, neither of them. George Bush had famously said he didn’t do the vision thing.” In short, “they weren’t visionaries, and nor were we.” 7 Hurd remembers that they played it safe, which was sensible and indeed his preference, but that they may have let a big opportunity go by.

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe