- Home

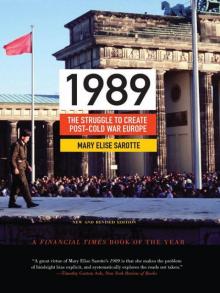

- Mary Elise Sarotte

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe Read online

ADDITIONAL PRAISE FOR 1989

“Professor Sarotte’s vivid account of the events in 1989–90 that brought about the unification of the two erstwhile German states is the most balanced, thoroughly researched, and gracefully written account of those events that I have encountered. It sets standards for accuracy and style of presentation that will be difficult for other scholars to meet, much less surpass.” —Jack F. Matlock, Jr., former U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Cold War History

“The tragic hero of 1989, for Sarotte, is Gorbachev. He was, and is still seen by many Russians as a King Lear figure: a man prepared to give away what he should have retained to a west bent on extracting as much as possible from the Soviet collapse—under the cover of honeyed words and rhetoric of a new age.” —John Lloyd, Financial Times

“[A] truly great book.…[A] whodunit of world politics that uses sources from Germany, the U.S.A., Russia and other countries to reveal both the details and the drama of the year of German unification in an unprecedented fashion.” —Stefan Kornelius, Süddeutsche Zeitung

“This is a cracker of a read, a fast-paced policy study of a year that transformed Europe and the world.” —Australian

“Sarotte’s book is compact and highly interpretive. Yet Sarotte has thoroughly mastered the original source material in all the key countries. She distills it with great skill, constantly enlivening her account with a sensibility for what these changes meant in life and culture. Hers is now the best one-volume work on Germany’s unification available. It contains the clearest understanding to date of the extraordinary juggling performance of Kohl.” —Philip D. Zelikow, Foreign Affairs

“Much the most exciting of these books [on the end of the Cold War] is Mary Elise Sarotte’s 1989. In contrast to the other authors, Sarotte treats the uprisings and collapses of that year as a prelude to the biggest change of all: ‘the struggle to create post-Cold War Europe,’ as her subtitle puts it.…Sarotte [is] a lucid and compelling writer.” —Neal Ascherson, review of a group of books on 1989, London Review of Books

“Her analysis reminds readers once again that history does not just unfold and outcomes are not preordained… Stimulating reading for a general audience, students, and faculty/researchers.” —H.A. Welsh, Choice

“What if someone wrote a history that told the story from all sides, one that drew not only on memoirs and press accounts and the earlier work of scholars but also on the archives of nearly all the principal parties to the conflict, a history that included interviews with the diplomats, politicians, and activists who took part in events? And what if someone wrote this history analytically, parsing out the major decisions and events, remaining sensitive to the grays that shade human behavior, and avoiding definitive, black-and-white judgments designed to score political points? Mary Elise Sarotte…has written such a history.” —William W. Finan, Jr., Current History

“One of her many interesting themes is the question of how, in February 1990, the U.S. Secretary of State James Baker informally offered Gorbachev an undertaking that even though the unified Germany was to belong to NATO, the alliance’s jurisdiction ‘would not shift one inch eastward.’ However, the haste with which Poland and other ex-Warsaw Pact states were drawn into NATO… did much to compromise the chances of incorporating a chastened and susceptible Russia into a genuinely harmonious new world order—one of many telling arguments in Sarotte’s lucid and thoughtful book.” —Roger Morgan, International Affairs

“The prose and style are lucid.…[1989] is valuable to students, academics and general readers alike in learning more about these epochal happenings.…[T]his is an excellent work which is likely to become a key text for this period.” —Alex Spelling, Diplomacy and Statecraft

“Sarotte’s thoughtful conclusions are supported by prodigious scholarship… [she] is an excellent writer and never allows the narrative to flag.” —Tom Buchanan, English Historical Review

“Using multiple data from interviews with historical figures involved, biographies and extensive archival sources, she recounts the conversations, communiqués and personalities central to the events. This is a major contribution to scholarship in this field.” —Larry Ray, European History Quarterly

“Sarotte’s outstanding book shows that Europe’s prefab post-1989 order was a messy improvisation, but at no point during the collapse of communism did conditions favorable to the alternatives cohere.” —Richard Gowan, International Journal

“[Sarotte’s] highly engaging, well-paced account heightens the reader’s attention by making the high stakes of the negotiations clear, humanizing her principal actors, and capturing the mood and intrigue of the diplomacy.” —Sarah Snyder, Journal of Cold War Studies

“The author embeds her interpretation in a sharp-eyed, fluent narrative of 1989–1990 that sees the realpolitik behind the stirring upheavals.…[S]he offers a smart and canny analysis of the birth of our not-so-new world order.” —Publishers Weekly

1989

PRINCETON STUDIES IN INTERNATIONAL HISTORY AND POLITICS

G. John Ikenberry and Marc Trachtenberg, series editors

RECENT TITLES

Economic Interdependence and War by Dale C. Copeland

Knowing the Adversary: Leaders, Intelligence, and Assessment of Intentions in International Relations, by Keren Yarhi-Milo

Nuclear Strategy in the Modern Era: Regional Powers and International Conflict by Vipin Narang

The Cold War and After: History, Theory, and the Logic of International Politics by Marc Trachtenberg

America’s Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy, Expanded Edition by Tony Smith

Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American World Order by G. John Ikenberry

Worse Than a Monolith: Alliance Politics and Problems of Coercive Diplomacy in Asia by Thomas J. Christensen

Politics and Strategy: Partisan Ambition and American Statecraft by Peter Trubowitz

The Clash of Ideas in World Politics: Transnational Networks, States, and Regime Change, 1510–2010 by John M. Owen IV

How Enemies Become Friends: The Sources of Stable Peace by Charles A. Kupchan

1989: The Struggle to Create Post–Cold War Europe by Mary Elise Sarotte

The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change by Daniel H. Nexon

Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China`s Territorial Disputes by M. Taylor Fravel

The Sino-Soviet Split: Cold War in the Communist World by Lorenz M. Lüthi

Nuclear Logics: Contrasting Paths in East Asia and the Middle East by Etel Solingen

Social States: China in International Institutions, 1980–2000 by Alastair Iain Johnston

Appeasing Bankers: Financial Caution on the Road to War by Jonathan Kirshner

The Politics of Secularism in International Relations by Elizabeth Shakman Hurd

Unanswered Threats: Political Constraints on the Balance of Power by Randall L. Schweller

Copyright 2009 © by Mary Elise Sarotte

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton,

New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock,

Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

First paperback printing, 2011

Third paperback printing, with a new afterword by the auth

or, 2014

Library of Congress Control Number 2014945656

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Times and DIN 1451

Printed on acid-free paper. ∞

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

FOR MJS

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

ix

Preface: A Brief Note on Scholarship and Sources

xi

Abbreviations

xvi

INTRODUCTION

Creating Post–Cold War Europe: 1989 and the Architecture of Order

1

CHAPTER 1

What Changes in Summer and Autumn 1989?

11

Tiananmen Fails to Transfer

16

The Americans Step Back

22

The Status Quo Ceases to Convince

25

East German Self-Confidence Rises

28

Television Transforms Reality

38

CHAPTER 2

Restoring Four-Power Rights, Reviving a Confederation in 1989

48

On the Night of November 9

50

What Next?

62

The Four (Occupying?) Powers

65

Candy, Fruit, and Sex

68

The Portugalov Push

70

Specters Revive

75

The Restoration and Revival Models Fall Apart

81

CHAPTER 3

Heroic Aspirations in 1990

88

The Round Table

92

Counterrevolution?

95

The Consequences of the Brush with a Stage of Terror

99

Emerging Controversy over Reparations and NATO

103

“NATO’s Jurisdiction Would Not Shift One Inch Eastward”

107

Property Pluralism

115

CHAPTER 4

Prefab Prevails

119

The Security Solution: Two plus Four Equals NATO

120

The Political Solution: Article 23

129

The Economic Solution: Monetary Union

132

The Election Campaign and the Ways of the Ward Heeler

135

The Results of March 18

142

Reassuring European Neighbors

145

CHAPTER 5

Securing Building Permits

150

The First Carrot: Money

152

The Washington Summit

160

The Second Carrot: NATO Reform

169

Breakthrough in Russia

177

Pay Any Price

186

CONCLUSION

The Legacy of 1989 and 1990

195

Counterfactuals

196

Consequences

201

AFTERWORD TO THE NEW EDITION

Revisiting 1989–1990 and the Origins of NATO Expansion

215

Introduction: Fading Memories

215

Bearing Unwelcome Tidings

216

Genscher’s Thinking on NATO Expansion to Eastern Europe in 1990

219

The Split Between Bush and Baker

221

Kohl and Gorbachev

223

The Consequences of Camp David

226

Conclusion: The Persistence of Preferred Memories

228

Acknowledgments

230

Notes

234

Bibliography

306

Index

336

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

1.1. Selected Major Cold War Borders and Cities

17

1.2. Cold War Europe

30

1.3. Divided Germany

38

1.4. West Berlin (American, British, and French Sectors) and East Berlin (Soviet Sector)

41

FIGURES

I.1. Barack Obama in Berlin, July 24, 2008. Courtesy of Getty Images.

2

I.2. Vladimir Putin, future leader of Russia, poses with his parents in 1985 just before departing for his KGB posting to Dresden, East Germany. Courtesy of Getty Images.

4

I.3. The Berlin Wall in front of the Brandenburg Gate, November 1989. Courtesy of Gerard Marlie/AFP/Getty Images.

10

1.1. A lone demonstrator blocks a column of tanks at the entrance to Tiananmen Square in Beijing, June 5, 1989. Photo by CNN via Getty Images.

19

1.2. Protest in Leipzig, East Germany, October 1989. Photo by Chris Niedenthal/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images.

21

1.3. Bärbel Bohley, former East German dissident leader, in 2004. Courtesy of Michael Urban/AFP/Getty Images.

34

1.4. The Bornholmer Street border crossing from East to West Berlin, in the early hours of November 10, 1989. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1989-1110-016. Photo by Jan Bauer.

44

2.1. President George Herbert Walker Bush, third from left, with his main advisers; from left to right, Chief of Staff John Sununu, Secretary of State James Baker, National Security Adviser Brent Scowcroft, Vice President Dan Quayle, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney, Deputy NSC Adviser Robert Gates, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Colin Powell, and Office of Management and Budget Director Richard Darman. Courtesy of Time and Life Pictures/Getty Images.

55

2.2. President François Mitterrand of France and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of the United Kingdom, circa 1986. Courtesy of Getty Images.

58

2.3. Former West German security adviser Horst Teltschik in 2006. Courtesy of Joerg Koch.

74

2.4. West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl in Dresden, with East German Minister President Hans Modrow (foreground), December 19, 1989. Courtesy of Patrick Hertzog/AFP/Getty Images.

84

3.1. Robert Havemann, East German dissident, in 1979. © dpa/Corbis.

90

3.2. Ulrike Poppe, East German dissident, in October 1989. © Alain Nogues/Corbis Sygma.

93

4.1. Former West German Chancellor Willy Brandt at a campaign rally in East Germany, March 11, 1990. Courtesy of Getty Images.

141

5.1. President Bush with his wife, Barbara, and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and his wife, Raisa, at the Washington Summit State Dinner. Courtesy of Time and Life Pictures/Getty Images.

166

5.2. Kohl and Gorbachev in the Caucasus. © Régis Bossu/Sygma/Corbis.

183

5.3. Gorbachev (center right) presides over the final signing of the 2 + 4 accord in Moscow by the six representatives of the countries involved (from left to right, the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, France, the GDR, and the FRG) on September 12, 1990. Courtesy of Vitaly Armand/AFP/Getty Images.

194

C.1. Gorbachev receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1990. Courtesy of Getty Images.

199

C.2. Ceremonial signing of the NATO-Russia Founding Act in Paris, with Russian President Boris Yeltsin (left) and NATO Secretary General Javier Solana, May 1997. © Pascal Le Segretain/Corbis Sygma.

207

C.3. The concert hall on Gendarmenmarkt in Berlin, decorated to celebrate the extension of the EU to Eastern Europe in May 2004. © Langevin Jacques/Corbis Sygma.

213

PREFACE

A BRIEF NOTE ON SCHOLARSHIP AND SOURCES

Before beginning,

I must acknowledge my scholarly debts to a number of previous authors and the places that provided the sources used in writing this book.

I am fortunate in that I have a rich body of literature to draw on, because many analysts have already devoted considerable time to 1989. A majority of them have seen that year as a moment of closure, most famously Francis Fukuyama, who called it the end of history even while it was unfolding. He and others have produced impressive studies tracing the Cold War’s trajectory toward its ultimate collapse and dissolution. Particularly worthwhile examples have come from the writers Michael Beschloss and Strobe Talbott, James Mann, and Don Oberdorfer, and the scholars Frédéric Bozo, Stephen Brooks and William Wohlforth, Archie Brown, Robert English, John Lewis Gaddis, Timothy Garton Ash, Richard Herrmann and Richard Ned Lebow, Hans-Hermann Hertle, Robert Hutchings, Konrad Jarausch, Mark Kramer, Melvyn Leffler, Charles Maier, Gerhard Ritter, Andreas Rödder, Angela Stent, Bernd Stöver, and Stephen Szabo.1

As will become clear in the pages to follow, I see 1989 not as an end, but as a beginning. It created the international order that persists until today. The need to understand this nonviolent transition from the Cold War to the present is enormous, because we greatly prefer nonviolence to the alternative. As Gaddis has observed, the goal of historical scholarship “is not so much to predict the future as to prepare for it.” The process of studying history expands our range “of experience, both directly and vicariously, so that we can increase our skills, our stamina—and if all goes well, our wisdom. The principle is much the same whether one is working out in a gym, flying a 747 simulator,” or reading a historical study.2 Trying to understand the transition of 1989–90 is a singularly useful exercise, since it established durable new democracies. We therefore need to look closely at this transition as it represents a quintessential example of what political scientist G. John Ikenberry has rightly called a reordering moment.3

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe