- Home

- Mary Elise Sarotte

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe Page 21

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe Read online

Page 21

Fortunately, the 2 + 4 process could manage this because it was really “the ‘two by four’” process. In other words, the 2 + 4 mechanism was “in fact a lever to insert a united Germany in NATO whether the Soviets like it or not, but which gives them a role that ought to keep them out of a desperate corner.” The Soviets, whose power was “recoiling upon itself at … a frightening speed,” were gradually realizing this. Having “agreed at a weak moment,” they were now looking for ways to backtrack but were not finding any, even as the 2 + 4 meetings started on March 14.86 Although Sicherman did not say it, 2 + 4 also had the advantage of making the British and French feel more involved in the process of unifying Germany. Hurd found that it was particularly helpful in calming Thatcher, at least at first. Only after its implementation would the British realize that for all the expertise they brought to these talks, they were still not involved in the most important U.S.–West German decisions.87

These 2 + 4 meetings also had another advantage for the United States: they gave Washington “a handle on a German unification process that might otherwise be left to the tender mercies of the Germans and the Russians.” As Scowcroft feared, Moscow could potentially make Bonn an offer it couldn’t refuse, although Sicherman did not expect it.88 Rather, looking to the future, he predicted that other East European countries would not only accept Germany in NATO, they would even seek the benefits of membership for themselves. In other words, the transatlantic alliance “is the best way out of the German-Russian security dilemma and, with the Czech exception, the Hungarians and the Poles already see it.” He was right; they did see it that way. Already on February 20, 1990, Horn had suggested that his country, Hungary, should begin forging closer ties to NATO with a view to “‘eventually being integrated’” in its political bodies. At the time this suggestion was speculative, and tentative Polish feelers in the same direction initially received a cool reply. In the years to come, however, both countries would succeed in pressing for membership themselves.89

The Sicherman memo of 1990 rightly came to the conclusion that the United States “offers these nations great opportunities on all these scores.” But Washington had to be sure that “1) taking on the burden of ‘organizing’ this region is really a vital interest [and] 2) we have the means to do so. My answer tentatively is that we alone do not have the means but that NATO and the EC surely do.” Ross remembers that this memo triggered his own realization that in the long-term, the East European states were not going to feel secure until they were in NATO. Membership for them would also be a way to institutionalize democratic civilmilitary relations in these countries.90

Sicherman had argued that the Soviets would have to accept a united Germany in NATO eventually—but only if the East German elections showed clear support for it. A great deal was hanging on the March 18 outcome. The secretary general of NATO once again, as he so often did at key moments, suggested an idea that might improve matters and make Germany in NATO more palatable to the Soviet Union. Wörner was in regular touch with his old CDU party colleague Kohl throughout March 1990. Presumably in agreement with him, Wörner made public remarks on March 13 to the effect that Soviet troops could stay in Germany after it was unified. They would just have to agree on a departure date in the future.91

With all eyes focused on East Germany in the final days before the election, polling still suggested that the SPD would emerge as the strongest party, and perhaps even win an absolute majority.92 Ever since the opening of the wall, Brandt, the SPD’s greatest statesman, had been making numerous personal appearances in the GDR—although he was seventy-six years old and only the honorary party chair. A former member of the resistance to Hitler and the first chancellor of the FRG from the Left, he had also become the first West German leader to visit the other half of divided Germany in 1970. Hundreds of East Germans had braved the Stasi to welcome him even then.93 For his efforts to ease the inhumanities of the German division, Brandt had received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1971. His dramatic successes and failures—Brandt had to resign in 1974 as a result of sex and spying scandals—eventually became the subject of an award-winning play, Democracy.94 In 1990, he was the most prominent member of the SPD to welcome unity. With no Stasi threat, hundreds of thousands of people turned out to hear him speak in places like Gotha and Leipzig.

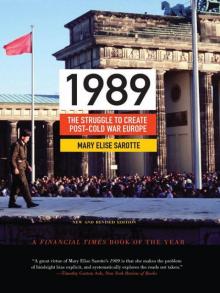

Fig. 4.1. Former West German Chancellor Willy Brandt at a campaign rally in East Germany, March 11, 1990. Courtesy of Getty Images.

Brandt, who had never ceased to be a German patriot, spoke warmly of unification; but he was not entirely representative of the SPD in this attitude. His party was ambivalent about unity and officially endorsed Article 146, meaning that the SPD preferred the slower path to unification. Its soon-to-be candidate for the West German chancellorship, Oskar Lafontaine, spoke in very different tones about unity. But Brandt, who wanted to be, once again, the voice that rose above the cacophony to show the way forward, pressed on with his remarks and speeches nonetheless. The warm reception that he received from the crowds showed that he personally still had appeal, even if the rest of the party’s hesitancy about rapid unification did not.

Despite Brandt’s enormous popularity and doubts among even CDU supporters about their chances, Kohl pushed on with his own campaign speeches throughout March.95 Given that the attendance was regularly in the hundreds of thousands, by the time of the last speech in front of three hundred thousand in Leipzig, he had personally addressed over a million people. He proudly told Bush this in a phone call on March 15. He also told Bush that the crowds had applauded loudly when he spoke about NATO and the alliance; “it is a pity you weren’t there, George.” The momentum carried his alliance through a crisis, when just days before the election Wolfgang Schnur, one of the CDU’s alliance partners, had to resign after evidence of his collaboration with the Stasi became public. Kohl told Bush that he truly did not know if his efforts had succeeded or not, or how the election would turn out. The chancellor just hoped for “a reasonable coalition.” 96 He was about to get a lot more than that.

THE RESULTS OF MARCH 18

To the astonishment of everyone, including the CDU itself, the Alliance for Germany won 48 percent of the popular vote. The fact that it almost reached an absolute majority in a pluralistic, multiparty election was quite an achievement. The CDU was particularly surprised by how well it had done in the regions of Thuringia and Saxony, which had had Socialist and Communist governments during the Weimar era (the last time they had been able to choose their leaders).97 With an election participation rate of over 93 percent, it represented a clear mandate. Kohl’s allies, headed by de Maizière, would dominate the future East German parliament. The SPD, with about 22 percent of the vote, would hold only eighty-eight seats out of the four-hundred-member Volkskammer in East Germany (Table 4.1)98

On the night of the election, the former dissident groups and the SPD were all in disbelief. Gerd Poppe personally won election to the Volkskammer, but his party, Alliance ’90, had gained only about 3 percent of the vote. Brandt was crushed and clearly looked every one of his seventy-six years. Visibly shaken by the result, he refused to appear for a scheduled on-air interview on ZDF, one of the two main West German channels. The television moderator was upset about this abrupt rebuff, remarking sarcastically, “well, sorry, the fact that he wanted to give an interview was on the schedule!” 99

Kohl, however, had sympathy for Brandt’s anguish. The events of 1989 and their shared desire for Germany unity caused the superstars of the Left and Right to develop a friendship in the little time that Brandt had left to live after 1990. Kohl believed that Brandt, with his deep personal desire for unification, had become an uncomfortable exception within his own party, and was understandably frustrated by the SPD’s failure to seize the chance to shape the future in 1990. The chancellor concluded that Brandt, who already on November 10 had called for the two Germanies to grow together, correctly sensed the East German mood when the rest of the party had not. Two years later, as Brandt neared d

eath, Kohl was one of the last visitors he would receive, and the elder former chancellor asked the younger to organize his funeral.100

TABLE 4.1

Election Results in East Germany on March 18, 1990

Name of Party or Alliance

Percentage of Vote

Seats in Volkskammer

Alliance for Germany (CDU and smaller affiliates)

48.0%

192

SPD

21.9%

88

PDS (formerly SED)

16.4%

66

Numerous smaller parties, including Eastern liberals and groups organized by former dissidents

13.7%

54

Participation: 93.4% of eligible voters

Source: DESE

The election result represented more than the competition between the two titans of West German politics, though. East German voters had a clear choice between the various models for the future. If they liked the concept of restoration, they could vote for the SED/PDS. If they liked the idea of moving slowly toward unity under Article 146 and reviving confederative structures in the meantime, they could vote for the SPD. If they liked heroic visions of the future, including a revitalized socialism as well as pan-European political and security structures, they could vote for the very dissidents who had headed the 1989 revolution and drafted a new constitution. Or if they believed that the prefabricated structures of the West German political and economic system should be installed in new Eastern states, they could vote for the CDU. On March 18, they chose in overwhelming numbers to do the latter. When the election results hit the news that evening, it was apparent to the world that Kohl now had enormous leverage.

Kohl lost no time in moving forward and using it. Although the chancellor celebrated with friends and colleagues into the early hours of Monday over champagne at an Italian restaurant, by Tuesday he was fully back to business and strategizing with Bush. The U.S. president congratulated the chancellor, telling him that he was “a hell of a campaigner!” Kohl pointed out that Bonn now had an entirely new level of support and legitimization for getting a united Germany into NATO. This legitimacy would help him both at home and abroad; now he had more leverage to contradict Genscher’s ongoing attempts to limit NATO expansion, which Kohl had still endorsed in February.101

His victory would also enable him to solve the conflict with Poland. Mazowiecki was about to visit Washington, and Kohl asked Bush to pass on a message to the Polish leader. “Please tell him I want to help him be successful, but I also have to be sure I am successful with my policies in my own country. I don’t usually say that publicly, but the election results also have a bearing on these questions.” Neither the chancellor nor the president agreed with a Polish request that the 2 + 4 talks should take place in Warsaw, but Kohl was ready to negotiate the wording of a future border agreement. “I am firmly determined to accept the Oder-Neisse border. I am not hiding anything … there is no secrecy.” Now that he had won the election, he had more room to maneuver, and it was time to resolve the border issue.102 On April 4, he would write to Mazowiecki directly, offering to begin negotiating a treaty. By the end of April, the Polish foreign minister had made it clear to Bonn that Warsaw was willing to compromise in the interests of signing such a treaty.103 Although there would be ongoing tension over the details, the Polish border issue was on its way to being settled. An accord eventually signed on November 14, 1990, in Warsaw would declare the Oder-Neisse line to be the final German-Polish border.104

Speaking to Shevardnadze the same day that Bush talked to Kohl, Baker reported that the Soviet foreign minister “was more pensive than I have ever seen him before” about the German question. March had been a hard month for Gorbachev and his advisors. Nationalist problems had reached a new crisis point when Lithuania declared independence on March 11.105 Warsaw Pact members had failed to agree on a unified line toward NATO.106 Shevardnadze refused to discuss Europe with Baker, but did say that it “would be a big problem” if Germany were in NATO, and “we don’t know the answer to this problem.” The Soviet foreign minister was not so much worried about current German leaders as about what future German leaders might do with a powerful and united country. Baker concluded that both Shevardnadze and Gorbachev “seem to be genuinely wrestling with these problems, but have yet to fashion a coherent or confident response. They also have yet to shape their bottom lines.” 107

On the home front, within forty-eight hours of the election result, the process of institutional transfer got under way with a government declaration that economic and monetary union would take place by summer 1990; later, the day was set for July 1.108 The debate was now over how, not whether, the economic systems would be merged. Kohl’s minister of labor, Norbert Blüm, argued that anything other than the expected exchange rate of one to one would cause an intolerable level of social upheaval. The new East German leadership agreed with him. Yet the president of the Bundesbank, Karl-Otto Pöhl, felt certain that this would push costs to such an unbearable level for most East German firms that they would collapse.109

This process raised questions about other levels of economic integration. In other words, West Germany was going to extend its institutions to the East more or less as is; would the EC do the same? Now that Kohl had a mandate for quick reunification, the ways in which German and European integration were going to mesh had to be made clear. The chancellor was fortunate in that he had a strong personal rapport with Delors, the president of the European Commission. They shared a belief in the desirability of German unification, as did European Commission Vice President Martin Bangemann, even if they differed over details. Delors saw the changes in Europe as an opportunity to demonstrate the vitality and efficacy of the EC, and he did not want to let that chance slip away. He had said publicly in January that there was “a place for East Germany in the Community should it so wish,” by which he meant that the EC would be willing to deal directly with East Berlin.110 Delors organized a trade agreement between the EC and GDR, which was signed just in time for its own obsolescence, as it was superseded by German monetary and economic union. Kohl and Mitterrand, in contrast, disliked Delors’s idea of having both Germanies in the EC. They thought that it would make much more sense simply to allow the existing German member of the EC—the Federal Republic—to grow by seventeen million citizens. Here, at last, Kohl’s and Mitterrand’s interests coincided: Kohl wanted to subsume East Germany and unify it with the West, not elevate it to the status of an EC member, and Mitterrand agreed: he could see “only one Germany” in the EC. This would be their joint (and ultimately successful) goal.111

REASSURING EUROPEAN NEIGHBORS

But even if the existing West German state would simply expand, there were still a number of unresolved issues. Some EC members worried that Kohl might focus so much on national unification, he would have no time whatsoever for European integration.112 Poorer EC members were also beginning to wonder if they might lose their subsidies to the cause of East German reconstruction. The French foreign minister, Dumas, played on these worries by commenting publicly that while a united Germany might have a lot of “economic potential,” the future was not “entirely rosy” because there was so much economic recovery work ahead.113 And both Dumas and the British thought that there should be more attention paid to the Helsinki Final Act of the CSCE.114

As ever, Thatcher was particularly irritated by West Germany’s plans. Hurd and his colleagues at the Foreign Office had been unsuccessful in their ongoing attempts to convince her that rather than oppose unification, she should work (as Mitterrand was doing) to tie a united Germany firmly into Europe.115 Instead of taking this advice, Thatcher convened a group of advisers and academics at the prime minister’s country residence, Chequers, on the weekend after the East German election to assess what it meant for Britain and Europe. A summary of the meeting written by her private secretary, Powell, recalled that the group asked “how a cultured and cultivated nati

on had allowed itself to be brain-washed into barbarism. If it had happened once, could it not happen again?” According to Powell’s report—the accuracy of which was later disputed by participants—the group concluded that the “way in which the Germans currently … threw their weight around in the European Community suggested that a lot had still not changed.” Phrases like this meant that Powell’s summary was too controversial to remain secret—a subsequent investigation into illicit copying of the half-dozen originals of the report stopped when it found over a hundred copies—and it caused a scandal when it was eventually leaked and published in the national press over the summer.116 Even Washington was wondering how EC expansion would interact with its favored international institution, NATO. Baker worried that the “French want our military presence, without recognizing our political presence”; closer political unity in the EC might exacerbate that.117

Kohl used his newfound leverage, garnered in the election, to address these worries in late March and early April. In a meeting with the European Commission five days after the March 18 election (which Delors had helped him to arrange), he argued that German unity would actually promote, not slow down, European integration. Saying that a united Germany would be neither the “Fourth Reich” nor the elephant in the china shop, he assured his European partners that he was committed to moving European integration forward in a way that would not be costly to the EC.118

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe