- Home

- Mary Elise Sarotte

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe Page 12

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe Read online

Page 12

According to Teltschik, he and Kohl agreed that only an enormous streak of luck would make it possible to achieve these goals within a decade; they estimated that it would probably take much longer. Few observers at the time dared to disagree with them, although one particularly prescient U.S. State Department memo of December 14 concluded that events were pointing toward “rapid reunification” and that any kind of truly free government in the GDR “must have reunification as its first agenda item.” 94 For Kohl and his aides, confederation was a serious proposal; they had no idea how quickly they themselves would choose to drop it.

Once the substance was set, Kohl and his chancellery advisers faced another important decision: whether or not to release information about the proposal in advance. Daringly, the chancellor decided to tell almost no one about it before inserting it in the Bundestag session, and then use the time-honored strategy of asking for forgiveness rather than permission. Other than Bush, no one—not his friend Mitterrand, and not even his coalition partner Genscher—would receive word before it happened.

According to Teltschik, this decision was the start of a pattern. He and Kohl agreed that they could and should make necessary decisions on their own, but one person always had to be informed: Bush. As a result, Washington was the only place to receive information before the Bundestag session (and Kohl also spoke to Bush for half an hour on the day after).95 Writing in English, Kohl said that in 1989, just as in 1776, the highest goal was to ensure “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness!” 96 It was a wise rhetorical choice, associating himself implicitly with a previous generation that had sought to create a new political order and succeeded.

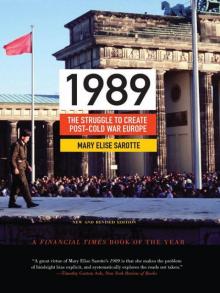

Fig. 2.3. Former West German security adviser Horst Teltschik in 2006. Courtesy of Joerg Koch.

Kohl’s message arrived in Washington too close to the start of his speech for the English translation to be completed before he began speaking. In assessing his words afterward, Walters, the U.S. ambassador in Bonn, pointed out “the fact that he [Kohl] felt confident about springing this approach without prior consultation is further evidence of the greater political self-assurance of an FRG which is already widely recognized as a weighty economic power.” 97 Nonetheless, Teltschik recalls, Bush and Scowcroft valued knowing how high they stood in Kohl’s priorities. Kohl and his close aides would also soon be dealing more openly with their U.S. peers in the White House than with their colleagues in their own Foreign Ministry.98

The strategy of asking for forgiveness rather than permission reflected Kohl’s need—indeed, the need of all heads of government facing crises beyond their borders—to balance between domestic and foreign politics. In light of what he thought he knew about Moscow’s intentions, he felt that he had to put forth his own plans for Germany. He believed that he sensed what East Germans wanted to hear, and that he could sell it in a way that would be acceptable to West Germans. But the allies and his neighbors were not going to like it, so he decided to present them with a fait accompli in light of the ongoing chaos in East Germany.99 And he was right. They were not happy.

In fact, Kohl did not even get through the announcement of the plan to the Bundestag without contest. When he explained that his offer of confederative structures was dependent on East Germany releasing all political prisoners, a member of the Green Party yelled sarcastically, “you’re not so petty when you’re dealing with Turkey!” 100 Moscow had other terms for Kohl’s behavior besides petty. Speaking with the leader of Italy, Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti (who was himself not jubilant about the ten points), Gorbachev complained the next day that Kohl was “playing the vengeful note for the forthcoming elections.” 101 His press spokesman, Gennady Gerasimov, told Western reporters that if Kohl had included an eleventh point—namely, a clear statement that Germany would not seek to restore its 1937 borders—then they would have thought more kindly of the program.102

And when Genscher visited Moscow a week later, even though—as Gorbachev was well aware—the foreign minister had had nothing to do with the Ten-Point-Program, the general secretary and Shevardnadze aimed their frustration at him nonetheless. According to Chernyaev, who attended the meeting, Gorbachev called Kohl’s actions “crude” and a violation of the sovereignty of East Germany. Shevardnadze suggested that Kohl was worse than a Nazi leader, saying that “even Hitler did not allow himself anything like that.” Gorbachev concluded that Bonn had “prepared a funeral for the European processes” and that Kohl was now marching to music in his own head.103 Genscher remembered this as the “unhappiest meeting” that he ever had with Gorbachev; the Soviet leader was so upset that it was, for the time being, simply not possible to discuss any important issues seriously.104

Teltschik prepared a summary report for his boss of world responses to the Ten-Point-Program. Mitterrand, understandably, was shocked to have been left in the dark. He had appeared with Kohl at the European Parliament, and the two had corresponded just one day before Kohl’s Ten-Point-Program speech.105 The French president had expressed support publicly, but added that the European peoples did not want to be confronted with decisions made in secret.

Teltschik personally defended Kohl on December 1 to Le Monde’s Bonn correspondent, Luc Rosenzweig. The West German pointed out to Rosenzweig, somewhat disingenuously, that Mitterrand would never ask Bonn for permission before making decisions on French national issues, so West Germany could hardly be expected to do so. But trying to make up for the affront, Teltschik spelled out what he really meant clearly. “The government of West Germany would now have to agree to practically any French initiative for Europe. If I were French, I would take advantage of that.” 106 Unification would mean that France would get more or less whatever it wanted in the arena of European integration. In other words, the doors to rapid European integration opened in December 1989, allowing a clear view of Maastricht on the horizon. Such a view held little charm for Thatcher, who did not share the French goal of expanding EC authority and competencies. Rather, Teltschik reported to Kohl that the current status quo gave Britain “a guarantee of stability on the continent,” and as a result any changes to it were frightening to the Brits.107

SPECTERS REVIVE

Bonn, or at least the chancellery, had now decided on a plan and a course of action. Kohl set about scheduling talks in East Germany to begin the construction of confederative structures. He agreed to meet the person now in charge of the GDR, Modrow, in Dresden in December. Given that Mitterrand still wanted to carry out a December 21, 1989, visit to East Germany that had been initiated years before, Kohl decided to travel east first, so the date of December 19 was booked.

But London, Moscow, Paris, and Washington were still struggling with their own models for the future. As Zelikow and Rice recount, within the Western alliance there was enormous tension over the various options. By late November, “the U.S. government and its key allies were avoiding an open clash over Germany only because they could all agree that they shared a short-term national interest in seeing political reform continue in the GDR.” 108

Bush and Gorbachev, meeting on ships in the exceptionally stormy seas around Malta on the weekend of December 2 and 3, made little headway on what to do about Germany. Bush went to Malta in a cautious frame of mind. He had received private advice from former President Richard Nixon that he found worthwhile and shared with Baker, Scowcroft, and others. Nixon argued that it had been “a mistake for Reagan to put his arm around Gorbachev physically and rhetorically in Red Square.” The former president strongly advised Bush against doing the same in the Mediterranean. “For you to leave a similar impression after your meetings in Malta,” cautioned Nixon, “would only add credence to the mistaken idea so emotionally being propounded by the prestigious Beltway media that because the wall is coming down, we have no differences with Gorbachev that can’t be settled by a few friendly meetings and warm handshakes.” Nixon maintained that Gorbachev’s real goal was denuclearization, and “the withdrawal of all foreign troops from Western and Eastern Europe. Thi

s is, of course, simply the son of Reykjavik, when [sic] he got Reagan to agree to the elimination of all nuclear weapons within ten years.” Nixon also thought that Bush should take a hard line and update the Monroe Doctrine, telling Gorbachev that “any sale of arms to a government in the Western Hemisphere which is unfriendly to the United States is simply unacceptable.” Nixon’s conclusion was as follows: “I would strongly urge that you indicate that you are not going to negotiate German reunification or the future of NATO with Gorbachev.” Bush asked his advisers to discuss this “interesting thinking” with him as part of the preparation for Malta.109

Baker had received advice as well, in his case in-house from the man he had chosen to be his counselor at the State Department, Zoellick. Preparing Baker not only for Malta but also for the NATO summit that would immediately follow it, Zoellick wrote that the secretary’s overall theme should be the need for a “New Atlanticism and a New Europe that reaches farther East.” Yet the “architecture of the New Atlanticism and New Europe should not try to develop one overarching structure. Instead, it will rely on a number of complementary institutions that will be mutually reinforcing,” including NATO, the CSCE, the WEU [West European Union], and the Council of Europe.110

According to both Baker’s and Chernyaev’s notes from the actual summit, their bosses neither made decisions on Germany nor talked much about it.111 This was due in part to the cancellation of a number of events because of the extremely rough weather. It would eventually become too dangerous to move between the U.S. and Soviet ships in the rough seas, and crew members would end up enjoying lavish rations when VIP meals were canceled.

It was not just the weather that dampened events, though. There was also reluctance on the part of the Bush delegation to make big changes. In his opening statement, Bush echoed Nixon’s letter, saying, “I do not propose that we negotiate here.” Rather, according to Baker, the president suggested that they hear each other’s opinions and then move forward “over a longer time-frame.” 112 The focus was on troop reductions and arms control measures in both the nuclear and conventional realms. Gorbachev told Bush that under “no circumstances” would the Soviet Union “begin a war.” Bush assured Gorbachev that the United States would avoid provocative actions with regard to questions of German unification. Both hoped that the Vienna talks, which would eventually yield the Conventional Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty, would succeed. When Germany did come up, Bush said “we can’t be asked to disapprove of reunification.” Gorbachev did not push the matter.113

More important than the Malta summit was a meeting that took place immediately after, on the night of Sunday, December 3, 1989, in Laeken outside of Brussels. Bush went directly from Malta to Brussels for the NATO session starting there the next day. Kohl arrived early as well. The two met for dinner; it was their first face-to-face meeting since the wall had come down.114 Bush would have been well within his rights to be displeased with Kohl. The West German had launched a major surprise initiative, with no consultation, just days before Bush had to meet not only the Soviet leader but all the heads of NATO. He thereby put Bush in the position of going to a number of meetings with major world leaders, all of whom would want to know Bush’s opinion of Kohl’s plan, without giving the U.S. president any chance to have input into it. Being required to discuss an unfamiliar proposal on short notice—one that he knew nothing about before it appeared, and had no role in creating—might be common tasking for a Washington subordinate, but not for a president. It clearly showed that the initiative came from Bonn, not Washington. And Bush had just endured a tiring summit meeting on ships in a storm. Kohl came to Laeken prepared to justify himself.115

Remarkably, far from being Kohl’s comeuppance, the Laeken dinner became, in Scowcroft’s words, a major “turning point.” It was where Bush decided to give the strongest possible support to the chancellor’s plans. Scowcroft, who was there, remembers watching it happen. Kohl’s plans and vision deeply impressed the president, and after hearing them, Bush made remarks along the lines of, I’m with you, go for it. Scowcroft recalls his jaw dropping open as he saw the future of U.S. foreign policy take shape. Bush remarked afterward that he realized he trusted Kohl “not to lead the Germans down a special, separate path.” Zelikow recalls that Bush was, at heart, a deeply emotional man who trusted his instincts. In Laeken, those instincts were telling him that Kohl was right.116

How did the chancellor win the U.S. president over? By giving him a convincing description of the problems on the ground and the solutions he wanted to apply. Bush listened sympathetically as Kohl explained that East Germany was in meltdown. “Can I tell you about what happened today in the GDR? Everyone has resigned.” The extent of corruption among the leadership was just becoming known, and it was clear that a dangerous backlash was mounting. Scowcroft, hearing how fragile East Germany really was, would later wonder how the West had gotten it so wrong and been so worried about the Warsaw Pact.117 Kohl continued, saying that “we cannot afford to pay 100 DM for each visitor anymore. It already amounts to 1.8 billion.”

Then the chancellor began talking about the Ten-Point-Program and made sure to say “thank you for your calm reception of my ideas.” The chancellor promised not to do anything “reckless.” Bush asked about attitudes to the ten points in both East and West Germany. Kohl said that East Germans needed more time to figure out what they wanted; but in West Germany, his political opponents were already denouncing the plan simply because it was his. And they were not alone; Thatcher was “rather reticent.” Bush interjected, “that is the understatement of the year.” Kohl, agreeing, said he didn’t understand why Thatcher was opposing unity instead of trying to get out in front of it. She should follow France’s example. “Mitterrand is wise,” Kohl continued, pointing out that the Frenchman knew how to find advantages in the process for his homeland. The two then discussed Gorbachev, and Kohl wanted to know if he had asked Bush for financial help. The president replied that no, Gorbachev was too proud to do so. In summary, their two-hour dinner conversation was wide-ranging and open. The effect that it had on Bush was apparent the next day, when his public comments at the NATO summit showed that he was strongly supportive of Kohl. Rather than echoing calls for caution, he said that it was time “to provide the architecture for continued change.” 118

Kohl’s Ten-Point-Program had a polarizing effect. Even as it caused Bush to respect Kohl as a strong leader, the other three powers became more worried because of the way in which he had blindsided everyone with it, including members of his own government. By December 8, Gorbachev was confident enough of British and French anger about it to threaten to hold a quadripartite meeting once again. He had Shevardnadze send a message “to propose to the three powers’ administration in West Berlin arranging [it] within the shortest possible time.” 119 He also delivered a speech to his Central Committee the next day that was highly critical of Kohl; Bonn assumed that West Germans, and not the people in the room, were the intended audience. Gorbachev was right in his assessment of British and French views. On that same day, December 8, Mitterrand and Thatcher spoke privately. According to the British record of the conversation, Mitterrand explained that he was “very worried about Germany” and that “the time had come for action. He and the Prime Minister needed to consider what role might be played by the Four Powers.” Thatcher agreed readily that the “Four Powers ought to meet soon” otherwise there “could be a total collapse of the system with increasing demands for reunification.” If that were to happen, “all the fixed points in Europe would collapse: the NATO front-line: the structure of NATO and the Warsaw Pact: Mr. Gorbachev’s hopes for reform.” She found that “we must have a structure to stop this happening and the only one available was the Four Power arrangement.” Mitterrand agreed, saying that he was particularly worried about Soviet troops in East Germany; if some kind of violence against them were to occur, “they would not doubt open fire.” Given all of the dangers, he concurred in her view that a four-power meet

ing was necessary.120

Either unable or unwilling to prevent the resurrection of this idea of restoring quadripartitism, and fearing a rift with London and Paris, Washington finally went along. Baker conducted a number of conversations on December 9, trying at least to make sure that the scope of action would be limited. He got agreement that the meeting would discuss only Berlin. “Hurd + Genscher said OK to go ahead. … U.K. wants to do at Amb[assadorial] level to push FRG down a bit. … Have Ministers in Berlin meet + discuss only Berlin,” read his handwritten notes from that day.121

The meeting took place in the very same Allied Control Commission building that had been used at the end of the war. Even the kind of language employed at the December 11 quadripartite meeting was extraordinary; the year could easily have been 1945. “Since we have emerged as the victors of the war, we have taken on the responsibility of providing for … a peaceful future,” intoned the Soviet ambassador to East Germany, Vyacheslav Kochemasov. He then tried to open a long conversation about “the way in which the four powers” would address the present issues—that is, not including the Germanies. Kochemasov also called for the institution of regular ambassadorial meetings.122 The U.S. participants (who had sent their proposed discussion topics to Bonn in advance, which was a break with previous four-power practice and an attempt to appease Kohl’s chagrin about being excluded) tried to keep the content of the discussions focused on Berlin. But the significance of the meeting was that it happened at all, not its content.

THE RESTORATION AND REVIVAL MODELS FALL APART

Even as American representatives took part, they knew that this was the way back, not the way forward. U.S. Ambassador Walters was embarrassed. He called photos of the attendees gathering in front of the old Allied headquarters the worst of the year.123 Added insult came from the fact that Baker himself carried out a trip to divided Berlin the day of the meeting and then gave a highly publicized press conference the next day, December 12. The combination of the four-power session, Baker’s presence in the city at the same time, a surprise meeting with East German leaders, his remarks at the press conference, and the fact that Kohl had to come to West Berlin to breakfast with Baker (rather than receiving him in Bonn) all looked like Kohl receiving a reprimand. It is no surprise that, as Baker notes in his memoirs, Kohl was “irritated.” The secretary’s public comments had been meant to convey the need for “a new architecture for a new era,” and a “New Europe and New Atlanticism.” But what hit the headlines were his remarks that the United States was interested in a “stable” process and “that is the political signal that we want to give with our presence here today.” Dan Rather, covering the event for CBS, called it “an unscheduled rescue mission for [the GDR’s] Communist prime minister.” Baker was the highest-ranking U.S. official ever to visit East Germany, and the timing of the visit looked like a clear signal. Press reports concluded that Baker had intended the trip as a slap in the face to Kohl’s plans for change.124

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe