- Home

- Mary Elise Sarotte

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe Page 27

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe Read online

Page 27

Meanwhile, a private conversation between Genscher and Gorbachev’s wife, Raisa, who had joined the group, also struck a note of warning. Pulling Genscher aside, she asked him in a low voice if he was fully aware of what her husband was risking. The Gorbachevs’ marriage seems to have been an exceptionally happy one, and it pained Raisa greatly to see Mikhail in danger. Essentially, she asked Genscher to save her trusting husband from himself. She made Genscher swear to deliver on any promises made there in the mountains. Genscher, taking her hand, replied solemnly that “we have learned the lessons of history in every aspect. I know very well what your husband is doing here. Everything will work out fine.” 151 Another hearty meal followed later, with yet more good Russian vodka for all.152

Monday, July 16, was less harmonious. Meeting in a large group, the delegation members went back and forth on the exact terms under which Moscow would let a united Germany join NATO. The biggest open questions surrounded the Soviet troops there: How long would they be allowed to stay? How much financial aid would Moscow get for their withdrawal? What limits would there be on NATO activity in the regions that they vacated? To the frustration of the West Germans, when they thought they had an agreement, suddenly a new statement would seem to contradict it. Kohl was certain that he and Gorbachev had agreed on a three to four year withdrawal period the day before, but in Archys the Soviet leader began speculating about five to seven years. Kohl pushed back, saying that they had agreed on three to four years already, and Gorbachev relented.153

Less evident was what kind of financial aid the Soviet Union would receive for the withdrawal. The West German delegation did not pay sufficient attention to strong hints from Gorbachev and his aides that it was to be an enormous amount. The Soviets suggested that it should cover many areas of the troops’ withdrawal, resettlement, and retraining back at home as well as the loss of Defense Ministry property. Genscher cut in to ask what, exactly, that property was, but Gorbachev responded only vaguely.154 Kohl, impatient to move on and thinking that it could be handled at a lower level—he would be proved wrong, as he and Gorbachev would have to settle the amount in contentious phone calls in September—replied that West Germany might be willing to help with some of these areas. Their two countries should set up teams to negotiate a bundle of accords.155 He thereby de facto delegated the details of funding for troop withdrawal to his finance minister, Waigel.

Kohl did focus, however, on trying to figure out the status of East German territory after troops withdrew and, by extension, what NATO could do there. At first, Gorbachev declared flatly that “NATO’s military structures” could not extend eastward.156 Genscher interjected that Germany had the right to select its own alliance (according to the Helsinki Principle, which Gorbachev had confirmed at the Washington summit) and that it would choose to join NATO.157 Gorbachev agreed, but it became clear in the course of the conversation that he did not want this agreement explicitly codified. He wanted as little as possible about the future of NATO to be put in writing.158 Why he felt this way is unclear. Perhaps he wanted to make sure that his enemies did not have written evidence, or perhaps he wanted to keep open some possibility for changes later. Whatever the reason, this hesitancy would have far-reaching consequences. His successors would search in vain for written guarantees that the price for German unity was a preemptive repudiation of any kind of NATO enlargement.

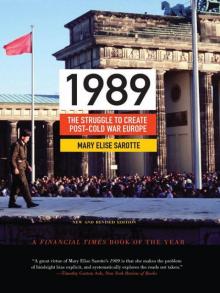

Fig. 5.2. Kohl and Gorbachev in the Caucasus. © Régis Bossu/Sygma/Corbis.

Genscher asked a number of detailed questions; in response to them, Gorbachev modified his position to say that NATO structures could not extend to the GDR as long as Soviet troops were there.159 But Shevardnadze seemed to contradict his boss when he interjected that even after Soviet troop withdrawal, there should be no NATO structures and especially no nuclear weapons.160 Gorbachev suggested a compromise, saying that he could envision both sides living with some kind of bilateral agreement that left the limits of NATO’s role in East German territory vague, but guaranteed that no steps would be taken to “diminish the security of the Soviet Union.” 161 He added that NATO’s nuclear weapons must be specifically banned from the area.162 German NATO troops could go in after withdrawal, as long as they had no nuclear weapons.163 For their part, Kohl and Genscher indicated that they would agree to a future ceiling of 370,000 troops in the Bundeswehr; as they had anticipated, this would eventually be codified in an annex to the CFE treaty.164

Kohl decided that he had enough to go public. He had conceded in only two respects: there would be no foreign troops and no nuclear weapons in East German territory. Otherwise, he had gotten everything that he wanted.165 There was still lingering uncertainty about exactly what NATO could do in the East German territory after Soviet troop withdrawal, but Kohl felt that it was not going to be a deal breaker down the road. Ironically, at the last minute, he would have more trouble with the Americans than with the Russians over this question.166

Even without complete clarity on that point, the press release would still be a sensation, once Kohl and his team could get it into the hands of their journalists. Reporters had been taken to a different location from the talks, were not happy about it, and were ravenous for news. When they all assembled for a press conference in the nearby Zheleznovodsk sanatorium later than afternoon, Kohl did not disappoint them. The chancellor started by asserting that the new Germany would maintain the existing borders of East and West Germany and include Berlin; this was aimed at Mazowiecki. Next, he explained that the four occupying powers would retire their remaining occupation rights and united Germany would regain full sovereignty. It would, according to the Helsinki Principle agreed on at the Washington summit, be able to choose its own alliance, but there would be a transition period of three to four years before Soviet withdrawal, and all occupying powers would stay in Berlin during the transition. A united Germany would renounce atomic, biological, and chemical weapons, and not send NATO troops to former East German territory while the Soviets were still there; but Bundeswehr and territorial defense forces that were not part of NATO could move in. There would be an upper limit on German forces after unity of 370,000. Kohl would make sure that East Germany was in accord with all of these terms. Finally, there would be bilateral talks about economic cooperation.167

This was big news. Television stations rushed to broadcast the story. “Germany Can Go into NATO” flashed the headline on one talk show, displaying happy images of Kohl and Gorbachev in casual clothing and scenic surroundings.168 The broadcast inspired a wide range of reactions; the farther away a viewer was from the site of the press conference, the happier he or she was about it. Halfway across the globe, Washington was thrilled. The press conference was the first that any Americans had heard of Kohl’s success; the White House would have to wait for details until Kohl was back in Bonn with secure communications. Bush issued an immediate statement nonetheless, in which he—apparently unintentionally—overstated what had in fact happened. The president welcomed the news, noting that he and Kohl had decided five months before that NATO’s military structures should extend to Eastern Germany. In fact, Kohl and Gorbachev had just agreed that almost none of NATO’s military structures could extend. There was thus a discrepancy between what transpired in Archys and what Bush told the world had happened there. This discrepancy would cause problems once it became obvious in the final days of the 2 + 4 talks. Meanwhile Baker, who was in transit to Europe for a newly important 2 + 4 meeting the next day in Paris, did his best to brief journalists on the basis of what he knew.169

In Warsaw, the Polish leadership realized that German unity now had Soviet blessing, and Poland had less leverage as a result. Mazowiecki and his advisers decided to reduce their demands correspondingly. At the Paris session of the 2 + 4, to which Poland had succeeded in getting an invitation, the Polish delegation dropped its calls for a peace treaty to World War II. It also agreed that a border treaty with the united Germany, which Warsaw had sought before unification, could be signed immediately afterward i

nstead.170 Kohl would later invite Mazowiecki to visit Bonn on November 8, 1990, signaling that they could finalize the treaty then, and that the united Germany would remove Article 23 entirely from its Basic Law. Bonn also showed a willingness to forgive more debt and ease payment terms on the remainder. The Polish border issue was finally going to be solved.171

As for Gorbachev’s colleagues and opponents watching in the Soviet Union itself, they were utterly aghast. They were already upset at receiving little or no information about the negotiations in Archys other than what was released to the public. Falin complained that the only papers that mattered were those exchanged between Chernyaev and Teltschik; he, Ryzhkov, Kryuchkov, and indeed all institutions of the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact were in the dark. Gorbachev had wanted to wave his magic wand once again, Falin concluded, and wondered aloud whether the Soviet leader had agreed with Kohl because he was a “masochist.” 172 Another adviser thought that by this point, Gorbachev was behaving like an emperor.173

Meanwhile, Kohl, Genscher, and their colleagues, flying home in their Boeing 707s with scores of journalists, popped the corks on bottles of German champagne. Genscher, who was not a well man, said that the exhilaration made him feel strong enough to “rip trees out of the ground with just bare hands.” 174 Teltschik was impressed at how well Kohl and Genscher had cooperated to win Gorbachev over. When the stakes could not be higher, these two leaders of German politics could put aside their differences and pull in harness together.175

Once they all got back to Bonn, Genscher went onward to Paris to meet Baker before the next 2 + 4 session, while the chancellor received a round of thunderous applause from journalists at a press conference.176 He also got hearty congratulations from Bush, with whom he spoke on Tuesday, July 17. (Scowcroft also sent a handwritten congratulatory note to Wörner, thanking him for all his help.)177 Kohl reported to Bush that Gorbachev had a lot of authority as a result of the party congress and he was willing to use it even when his advisers disagreed. Neither he nor Bush knew, of course, that Gorbachev would never have that much authority again, and his compromises in Archys would hasten his downfall. For now, the chancellor focused on what he had said at his sanatorium press conference (and sent a note about it to Mitterrand as well).178 Discussing what Gorbachev might expect in return, Kohl foolishly said that Gorbachev could not possibly expect another five billion DM.179 Kohl was right. Gorbachev did not expect another five. He expected more.

But for now, it felt very much as if the carrots had worked, and Kohl had found his happy ending.180 He had gotten all the necessary top-level decisions made, he thought. Now he could trust subordinates to solve the detailed problems. The 2 + 4 delegations would write a treaty that would restore sovereignty to Germany; joint East-West German talks would complete the internal legal documents needed for unification; and Waigel would figure out how much they would have to pay the Soviet Union for its permission. In the meantime, he and Teltschik went off on month-long vacations.

PAY ANY PRICE

It only looked like the end. There was, in fact, much drama left in the final act of 1990. In Moscow, Gorbachev’s opponents were not willing to accept what he had done in the Caucasus, especially with Ukraine and Belorussia causing new problems by trying to assert their own laws and sovereignty.181 Through a variety of means, hard-liners sought to extract as much advantage as possible in negotiations with the West before giving their final blessing to unity.

One day after Kohl’s triumphant press conference in the sanatorium, seemingly a high point in East-West relations, a CIA investigation concluded that Soviet military leaders were transferring billions of dollars worth of military equipment east of the Urals. Doing so exempted such equipment from the CFE Treaty that was still under negotiation, because that treaty would only cover the “Atlantic-to-Urals” (or ATTU) zone. These measures had begun possibly as early as January 1989 and seemed like the start of a long process.182 The investigatory report estimated that “7,700 tanks, 13,400 artillery pieces, and several hundred armored combat vehicles and aircraft that would be subject to destruction under [the] CFE” had already been sequestered out of the relevant zone. The problem was that proving it at the Vienna talks would be difficult. Given that negotiators were talking about an upper limit of just twenty thousand tanks and artillery pieces in the ATTU region, the amounts being moved were certainly nontrivial.183

And just two days after the sanatorium press conference, Ryzhkov sent Bonn the price tag for Gorbachev’s concession: over twenty billion DM. This amount would ostensibly fund the costs of keeping troops in the GDR until 1994, removing them to the Soviet Union bit by bit, building new homes for them and retraining them for civilian life, and compensating the USSR for the loss of its property in East Germany. Ryzhkov was already on record as saying that the united Germany should compensate the Soviet Union for all possible economic disadvantages that might result from unification, and his demands showed it.184 Gorbachev followed this up a few days later with yet another draft of a bilateral treaty.185

Kohl took advantage of his vacation to delay in responding to either of them for over a month. This gave the teams of people in Bonn working on internal unification issues more time to make unity a reality.186 Those teams needed to move as quickly as possible, since not only the economy but also the ruling coalition in East Germany were both deteriorating. Internal divisions were tearing de Maizière’s government apart, since he was more willing to follow Kohl’s lead than his partners were. The SPD was threatening to pull out altogether, and would eventually do so. The foreign minister, Meckel, remained stubbornly unwilling to give up his vision of a nuclear-free Germany as a neutral bridge between the East and West. De Maizière would eventually replace Meckel with himself.187 By the end of July, Schäuble was seriously concerned that he could become unable to complete the unity treaty at all, since there might be no government in East Berlin to sign it.188

As if that were not enough, at the start of August 1990, Iraq shocked the world by invading Kuwait. The United Nations rapidly passed Resolution 660, condemning the aggression and sending a green light to the Americans who wanted a decisive military response.189 Suddenly, Europe moved dramatically lower on the Bush administration’s priority list. Instead of Kohl looking to Bush for support, now the president would be sending Baker to ask for financial help in repelling the invasion. Kohl would respond generously, giving even more to the Gulf War effort than the Americans asked for.190

Kohl realized that he needed to push down hard on the accelerator. He sought unity as fast as possible, because otherwise he might lose it to a combination of hard-line resistance in Moscow, squabbling in East Berlin, and U.S. distraction. Whatever issues could not be resolved quickly must now be pushed aside and left for a united Germany to decide. The mission was to unite as quickly as possible. In his memoirs, Hurd recalls that he “never blamed [Kohl] for driving ahead with unification as fast as he could. That was legitimate leadership; in his position Thatcher would have done the same.” 191

Kohl was convinced that no cost would be too high. As Teltschik remembers, by this point Kohl and his advisers were clear that they would pay just about any price short of withdrawing from NATO to make unity happen. Teltschik was amazed that Moscow did not sense this and make more extensive demands at the eleventh hour, such as the removal of all U.S. nuclear weapons from German soil. Teltschik believes that even if Gorbachev had asked for a hundred billion DM as the price for unity at this point, Bonn would have found a way to pay it, so great was the opportunity at hand and the desire to seize it.192 It was also a matter of no small importance that all of this was taking place with an election just months away.193 The timing provided motivation, but also risks; the Soviet Union could have forced the West German electorate to choose between NATO and their national unity in an election year, and many FRG politicians would have been willing to let NATO go. In brief, Kohl’s worry was that if he did not get unity now, under known conditions, future alternatives would be m

uch worse.194

Kohl moved forward quickly and on a variety of fronts, even though he was ostensibly still on vacation. He struck an agreement with Delors to prevent any possible opposition in the EC. The two agreed that West Germany would be paying the costs for unification.195 This move had both European and domestic motivations; on the one hand, it was to prevent poorer EC members from complaining that they would lose out; on the other hand, it addressed domestic complaints from West Germans that they paid too much into the EC already, and would have to pay twice if they supported unity with both their domestic taxes and their EC contributions.196 Earlier that year, Kohl had confided in UK Foreign Minister Hurd that he thought the West German population was being greedy and churlish on this issue, and was simply unwilling to give up its luxurious lifestyle; as he put it, “people in the FRG were unwilling to make sacrifices for unification.”

There were also worrying signs of a developing backlash against East Germans. A poll in early 1990 showed a majority of West German respondents in favor of stopping immigration from the East entirely. The SPD’s candidate for chancellor, Lafontaine, played on that sentiment by saying that Easterners should only be allowed to come to the West if they could provide proof of a job offer and housing. He had won a record reelection victory in his home state of Saarland earlier in 1990 after famously deriding the chancellor’s aspirations as “Kohlonialism,” and believed that questioning the desirability of a German-German merger was a ticket to national success. He also doubted whether the West German status quo should be extended to the East without any thought as to whether the West “was on the right course.” 197

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe

1989- The Struggle to Create Post-Cold War Europe